The future of the earth as seen by the creatures of the micro-world Elucidating the ecosystem of symbiotic creatures

Shigeharu MORIYA, Unit Leader Biosphere Oriented Biology Research Unit

We know very little about the world of microbes.

The research group led by Shigeharu Moriya investigates the role of microbes by studying the organic compounds metabolized by microbes in symbiotic relationships, and the genes directly extracted from the environment where microbes live.

The research has started to reveal that microbes may hold the keys to solving a wide range of environmental problems, from the reduction of greenhouse gases to the depletion of natural resources such as fossil fuels.

Going deeper into the mysterious world of microbes

There are a vast number of organic compounds in the ecosystem, and synthesizing, breaking down, converting and circulating these compounds are jobs performed by the microorganisms that live on land and in water.

Yet we only know the biology of less than 1% of these microorganisms. It is quite possible that there are many phyla, or divisions (a category in biological classification), in the remaining 99%, of which we do not even know their existence. The Biosphere Oriented Biology Research Unit led by Shigeharu Moriya (the Moriya unit hereafter) is aiming to establish a technology to analyze these unknown microorganisms as well as to apply this technology to solve environmental problems.

Why is it that we still know so little about such a vast array of microorganisms? Moriya explains,

‘Many microorganisms have symbiotic relationships with other microorganisms in which they utilize each other’s organic compounds, created from cellular metabolism (metabolites), as nutrients, so it was difficult to extract and culture a single microorganism. That is why they have never been closely observed’.

The Moriya unit has been working to use new approaches other than cultivating cell cultures. For example, a multi-headed metabolites analysis of metabolome, or meta-transcriptome analysis by directly extracting messenger RNAs from the environment in which microorganisms live, and reading the expressed DNA information to identify their roles and functions. Or proteome analysis to elucidate the whole picture of proteins created by these DNA. The basic philosophy is to combine these methods and exploit them (meta-omics science) in order to elucidate the functions of genes that take on many roles in a living symbiotic system.

Bird’s eye view of the distribution process of the substances on Earth

Not only is the Moriya unit working toward finding solutions to protect the global environment through its investigations of the world of microorganisms, it is also working to construct a methodology that will help to create a truly zero-waste society. Moriya continues,

‘Our aim is to naturally create everything humanity needs for a sustainable system in which everything will go back to nature without any waste’.

The source of almost all energy on earth is sunlight. Plants use the energy of sunlight to grow, a process called photosynthesis, and to create the eco-system. Moriya explains,

‘A fossil fuel such as petroleum is based on carbon from organic matter which was accumulated over geological time, so the ultimate source goes back to the energy we receive from the sun. Microorganisms distribute the energy from the sun, which is fixed by plants, by converting it into various compounds and distributing it back into the natural word. I am captivated by my research on microorganisms because this mysterious process fascinates me so much’.

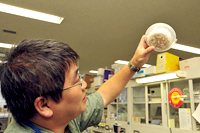

Observing laboratory termites

One of the microorganisms Moriyais concentrating on is found in termites, considered a pest by humans. In reality termites are beneficial insects because they eat the hard cellulose in dead wood, thereby helping to maintain forest ecosystems. And it is becoming clear that termites can digest cellulose because of a three-party symbiosis, involving a protistan living inside the termites and the microorganisms living in the protistan. It has also become clear through RIKEN’s studies, that the enzymes (proteins) involved in this process can be identified using genomic analyses. Moriya explains,

‘We can make bioethanol, hailed as an alternative energy source to replace fossil fuel, from wood-derived biomass such as agricultural waste, and thinned or fallen wood materials. When converting cellulose into glucose (glycosylation), it is necessary to pre-treat cellulose to get rid of lignin, a substance that inhibits glycosylation, and in the traditional method, the pre-treatment process needs a fossil fuel to drive the equipment. This is why this method could not achieve a high level of energy efficiency’.

‘On top of that, the traditional process required the cost and labor of adding a vast amount of cellulase, an enzyme used to hydrolyze cellulose’

‘On the other hand, if we can artificially produce the enzymes identified from the studies on termites and create a biomass glycosylation system within the facility, we will be able to use only eco-friendly biochemical energy for the glycosylation needed to create bioethanol’.

In this way it is not only possible to reduce the total energy required to produce bio fuel, but also to mitigate the impact of food shortages and rising food costs by using plant materials that are not useful for human consumption such as wood, instead of the traditional bioethanol raw materials of corn and sugar cane. Moriya also pointed out other possible applications from the termite study, for example, products that protect homes from termites, such as building materials that do not contain cellulose or the application of glycosylation-inhibiting paints to go on posts and beams.

Reaching out to the ocean ecosystem, the mineral mine of the sea

The Eco-tron

The Moriya unit studies not just termites but also other model systems aiming to contribute to production technologies for bio fuel and bio materials, such as medical materials to replace bone or skin. The unit started its investigation into marine microalgae and planktons in FY 2009 and the lab has an Eco-tron, an indoor experimental ecosystem.

‘The ocean is sometimes called the “unseen forest” or the “marine mine” because in it are creatures that produce silicon, the raw material for cement, and other raw materials such as polymers that can be applied in resins. For Japan, which is surrounded by the sea, successful research into this area means access to new energy resources in the future,’ Moriya says.

But as has already been explained, the mechanisms of how microorganisms work is almost unknown despite their importance in the environment. Moriya continues,

‘By understanding the relationships within the ecosystem and diagramming them, it is possible to understand on a global scale how substances derive from the energy of the sun. For example, we may eventually be able to identify the factors involved in climate change, including global warming, and improve the accuracy of future simulations. These developments should then raise the effectiveness of measures to deal with acid rain, global warming, drought and other environmental issues’.

Moriya concludes, ‘We would like to produce results that are useful for the world by understanding the natural world, a very complicated symbiosis, as comprehensively and inclusively as possible’.